How Libraries Are Creating Community Through Food

Across the country, libraries have long been trusted, accessible, and free repositories of resources and information, a democratized space for all. Library administrators look to see what a community needs or lacks “and how we can solve these problems,” says Jack Scott, outreach consultant for the Southern Adirondack Library System in New York.

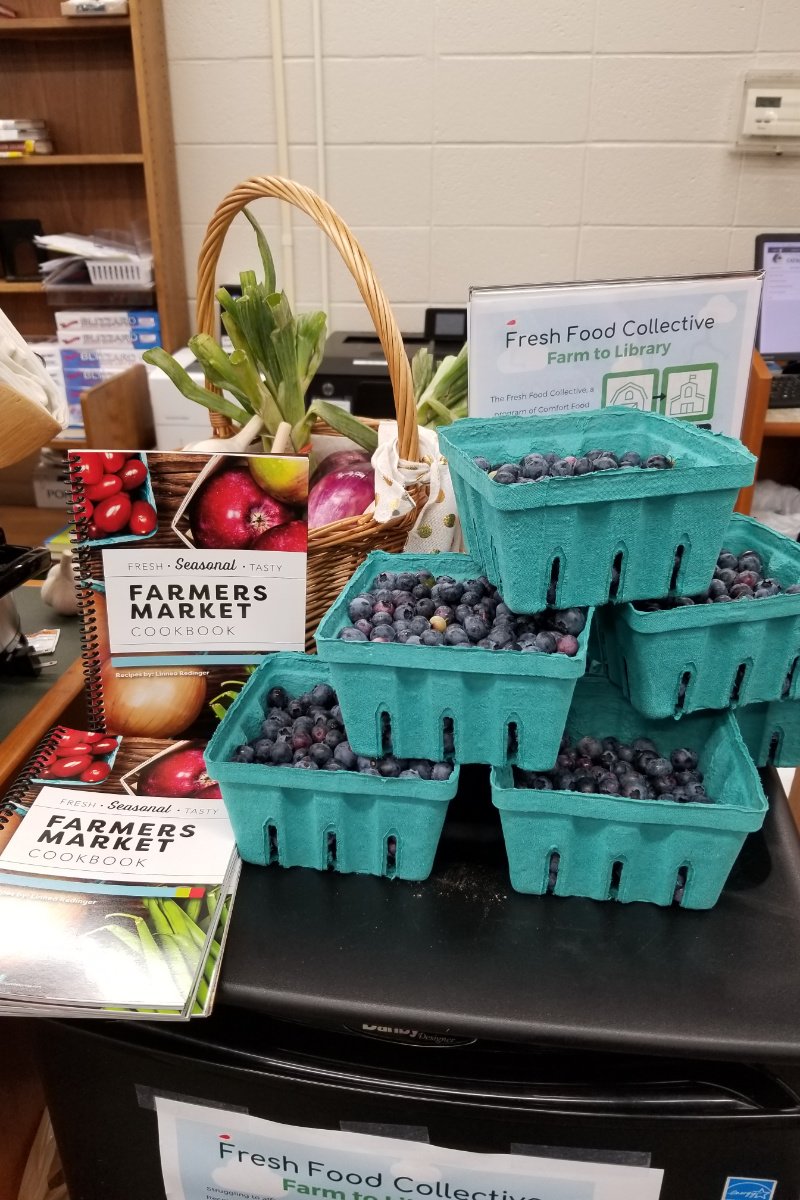

He oversees Farm-2-Library, which delivers rescued food to 13 libraries for locals to pick up, helping solve problems with food distribution in this rural region.

At the Terrytown Library outside New Orleans, culinary education has blossomed into two weekly children’s cooking classes serving 48 kids, adult culinary and nutrition classes, and a community teaching garden that produces vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers.

In the four years since the library began offering culinary education, branch visitation has increased, and physical circulation of materials such as books, DVDs, magazines, and the Library of Things collection has jumped 9.5 percent, says Bethany Lopreste, the library’s manager. The Library of Things allows patrons to sign out items used in daily living, such as kitchen equipment or home improvement tools.

Programs like these help people make proactive choices in their own lives, she added.

“Teaching someone how to cook, how to garden, and how to encourage and include their families to participate is really impactful.”

“Teaching someone how to cook, how to garden, and how to encourage and include their families to participate is really impactful,” Lopreste says.

Learning cooking and self-expression in a safe space are “life skills they can take forward with them,” says Athena Riesenberg, who runs a popular teen cooking program at the Des Moines Public Library’s Franklin branch. During National Poetry Month, for example, attendees baked fortune cookies and wrote their own fortunes. Riesenberg saw how the program fostered camaraderie among participants, one of whom is heading to culinary school after high school.

The Central Arkansas Library System, whose motto is “The Library, Rewritten,” views the library’s role as a community wellness and information hub. Librarians there are information specialists for the community’s day-to-day needs, explains Jessica Frazier-Emerson, coordinator of Be Mighty, an anti-hunger program serving 14 libraries in Little Rock.

According to the Public Library Association’s 2022 services survey, 31.6 percent of libraries say food insecurity is a need they currently address.

“Libraries are accessible, which makes them ideal for food and resource distribution,” Frazier-Emerson says. “They are also bound to only offer no cost and identification-free programming, which also lends to equitable food distribution.”

What Happens When Federal Funding Stops?

The Be Mighty program provides after-school and summer meals for children through the U.S. Department of Agriculture, application and interview assistance for public benefits such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), community refrigerators, little free pantries, nutrition and trauma-informed cooking classes, and free monthly bus passes.

With the recent federal cuts to SNAP benefits, however, Frazier-Emerson worries that she may have to reduce the number of branches that Be Mighty serves.

Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill didn’t cut funding to the Child and Adult Care Food Program or the SUN Meals, which supply meals to the Be Mighty sites, but Frazier-Emerson is unsure the programs will remain unscathed.

SNAP-Ed, a federal grant program that teaches SNAP recipients how to stretch their SNAP dollars and cook healthy meals, has had its funding eliminated. SNAP-Ed supported some Be Mighty partners, including Arkansas Hunger Relief Alliance, so Be Mighty now offers fewer offsite cooking and nutrition classes.

There are no provisions in the federal bill that directly affect library funding nationally, but the burden it adds on state and local governments imperils support for libraries and other essential infrastructure. Separately, though, the federal government withheld funding earlier this year from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), which funnels money to state libraries to use and distribute. And the greater concern is for 2026—when IMLS will be eliminated.

The Schuylerville Library in Schuylerville, New York, regularly distributes fresh fruit and cookbooks. (Photo courtesy of Farm-2-Library)

As a result, the New York State Library anticipates losing $8.1 million. At the Southern Adirondack Library System, operations could be crippled, since the funding supports 55 of 80 jobs, including those responsible for processing construction grants, Scott says. Many projects could remain incomplete.

In Arkansas, smaller libraries will feel the greatest impact because they won’t be able to purchase their own databases or digital platforms without the funding, says Tameka Lee, communications director at the Central Arkansas Library System. “Cuts could mean fewer materials and less access for communities that rely on libraries,” she says.